Patrons of the Arts in the 14th and 15th Century Included

During the Renaissance, about works of fine fine art were deputed and paid for by rulers, religious and civic institutions, and the wealthy. Producing statues, frescoes, altarpieces, and portraits were just some of the ways artists made a living. For the more modest client, at that place were ready-fabricated items such as plaques and figurines. Different today, the Renaissance artist was often expected to sacrifice their own creative sentiments and produce precisely what the customer ordered or expected. Contracts were drawn upwards for commissions which stipulated the last price, the timescale, the quantity of precious materials to be used, and perhaps fifty-fifty included an illustration of the work to be undertaken. Litigations were not uncommon but, at least, a successful piece helped spread an artist's reputation to the point where they might be able to have more than command over their work.

Federico da Montefeltro by Piero della Francesca

Who Were the Patrons of Art?

During the Renaissance, it was the usual practice for artists to only produce works once they had been asked to practice so by a specific heir-apparent in a organisation of patronage known equally mecenatismo. As the skills required were uncommon, the materials costly, and the fourth dimension needed oft long, most works of art were expensive to produce. Consequently, the customers of an creative person's workshop were typically rulers of cities or dukedoms, the Popes, male and female aristocrats, bankers, successful merchants, notaries, higher members of the clergy, religious orders, and borough regime and organisations like guilds, hospitals, and confraternities. Such customers were keen not only to environment their daily lives and buildings with nice things simply also to demonstrate to others their wealth, skilful taste, and piety.

At that place was a peachy rivalry between cities like Florence, Venice, Mantua, & Siena and they hoped whatsoever new fine art produced would raise their status in Italia & Abroad.

Rulers of cities like the Medici in Florence and the Gonzaga in Mantua wanted to portray themselves and their family unit as successful and then they were keen to be associated with, for example, heroes of the past, real or mythological. Popes and churches, in contrast, were eager for art to help spread the message of Christianity by providing visual stories even the illiterate could empathise. During the Renaissance in Italy, it also became important for cities as a whole to cultivate a certain graphic symbol and image. In that location was a groovy rivalry between cities like Florence, Venice, Mantua, and Siena, and they hoped any new art produced would enhance their status within Italian republic or fifty-fifty beyond. Publicly deputed works might include portraits of a city'southward rulers (past and present), statues of military machine leaders, or representations of classical figures specially associated with that city (for example, Male monarch David for Florence). For the aforementioned reasons, cities frequently tried to poach renowned artists away from one urban center to work in their city instead. This revolving market of artists too explains why, particularly in Italy with its many contained city-states, artists were always very keen to sign their work and and so contribute to their own burgeoning reputation.

Baldassare Castiglione by Raphael

Rulers of cities, once they had establish themselves a good artist, might go along him at their court indefinitely for a keen number of works. A 'courtroom artist' was more than just a painter and could be involved in anything remotely artistic, from decorating a chamber to designing the liveries and flags of their patron'south army. For the very best artists, payment for their work at a particular courtroom could arrive across mere cash and include tax breaks, deluxe residences, patches of forest, and titles. This was but likewise because the majority of surviving correspondence we have from such artists as Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 CE) and Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431-1506 CE) involves respectful but repeated demands for the bacon their illustrious, yet tight-fisted patrons, had originally promised them.

Whoever the client of Renaissance art, they could be very item virtually what the finished commodity looked like.

Modest art, say a pocket-sized votive statue or plaque, was within the means of more humble citizens, just such purchases would have been only for special occasions. When people got married, they might employ an creative person to decorate a chest, some parts of a room, or a fine particular of furniture in their new home. Relief plaques to get out in churches in thanks for a happy occurrence in their lives was a common purchase, too, for ordinary folk. Such plaques would have been one of the few types of art produced in larger quantities and made readily available 'over the counter'. Other options for cheaper fine art included secondhand dealers or those workshops which offered such minor items every bit engraving prints, pennants, and playing cards which were ready for auction only could exist personalised past, for example, adding a family unit coat of arms or a name to them.

Expectations & Contracts

Whoever the client of Renaissance art, they could be very item about what the finished article looked like. This was considering art was not merely produced for aesthetic reasons merely to convey meaning, as mentioned above. It was no good if a religious order paid for a fresco of their founding saint simply to detect the finished artwork contained an unrecognisable effigy. Simply put, artists could exist imaginative just non go so far from convention that nobody knew what the work meant or represented. The re-interest in classical literature and art which was such an important part of the Renaissance only emphasised this requirement. The wealthy possessed a common language of history regarding who was who, who did what, and what attributes they had in fine art. For example, Jesus Christ has long pilus, Diana carries a spear or bow, and Saint Francis must accept some animals nearby. Indeed, a painting packed with classical references was highly desirable every bit it created a chat slice for dinner guests, allowing the well-educated to display their deeper cognition of artifact. The Primavera painting by Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510 CE), commissioned past Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici, is an excellent and subtle case of this common language of symbolism.

Primavera past Botticelli

As a consequence of the expectation of patrons, and in gild to avoid disappointment, contracts were unremarkably drawn up between artist and patron. The design, whether of a statue, painting, baptistery font, or tomb, might be agreed on in detail beforehand. There could even be a small-scale scale model or a sketch fabricated, which and so became a formal part of the contract. Below is an extract from a contract signed in Padua in 1466 CE which included a sketch:

Let it exist manifest to anyone who will read this paper that Mr Bernardo de Lazzaro had contracted with Primary Pietro Calzetta, the painter, to paint a chapel in the church of St. Anthony which is known as the chapel of the Eucharist. In this chapel he is to fresco the ceiling with four prophets or Evangelists against a bluish background with stars in fine gold. All the leaves of marble which are in that chapel should also be painted with fine gilt and blueish as should the figures of marble and their columns which are carved there…In the said altarpiece, Principal Pietro is to pigment a history similar to that in the design which is on this sheet…He is to brand it similar to this but to make more things than are in the said design…Master Pietro promises to end all the piece of work written to a higher place by next Easter and promises that all the work will be well made and polished and promises to ensure that the said work will be skillful, solid, and sufficient for at least twenty-five years and in case of any defect in his work he will be obliged to pay both the impairment and the interest on the work…

(Welch, 104)

The fees for a project were set out in the contract and, as in the instance higher up, the completion date was established, fifty-fifty if negotiations might go on long later to amend the contract. Missing the promised delivery date was perhaps the most common reason for litigation between patrons and artists. Some works necessitated the utilise of expensive materials (gold leaf, silver inlay, or item dyes, for example) and these might be limited in quantity by the contract to avert the artist overindulging and going over budget. In the case of goldwork or a fine marble sculpture, the minimum weight of the finished work could exist specified in the contract. For paintings, the price of the frame might be included in the contract, an item that oft cost more than than the painting itself. There might even be a get-out clause that the patron could avoid paying altogether if the finished piece did non proceeds favour with a console of contained art experts. After a contract was signed, a copy was each kept past the patron, artist, and public notary.

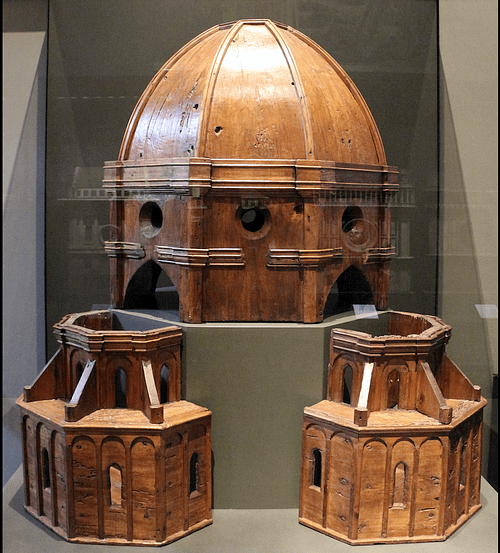

Original Model for the Dome of Florence's Cathedral

Post-obit the Project

Once the terms and conditions were settled, the creative person might still face some interference from his patron every bit the project developed into a reality. Civic authorities could exist the well-nigh demanding of all patrons every bit elected or appointed committees (opere) discussed the project in detail, perhaps held a competition to run into which creative person would exercise the job, signed the contract, and so, subsequently all that, established a special group to monitor the work throughout its execution. A particular trouble with opere was that their members changed periodically (although non their master, the operaio) so commissions, although non perhaps cancelled, could be seen as less important or too expensive by different officials from those who originally started the project. Fees became an ongoing issue for Donatello (c. 1386-1466 CE) with his Gattamelata in Padua, a bronze equestrian statue of the mercenary leader (condottiere) Erasmo da Narni (1370-1443 CE), and this despite Narni having left in his will a provision for just such a statue.

Some patrons were very detail indeed. In a letter from Isabella d'Este (1474-1539 CE), wife of Gianfrancesco Two Gonzaga (1466-1519 CE), then ruler of Mantua, to Pietro Perugino (c. 1450-1523 CE), the painter was left very little margin for imagination in his painting the Battle between Love and Chastity. Isabella writes:

Our poetic invention, which we greatly want to see painted by you, is a battle of Chastity and Lasciviousness, that is to say, Pallas and Diana fighting vigorously confronting Venus and Cupid. And Pallas should seem about to have vanquished Cupid, having cleaved his golden arrow and bandage his silver bow underfoot; with one hand she is holding him by the cast which the bullheaded boy has before his eyes, and with the other she is lifting her lance and about to kill him…

the alphabetic character continues similar this for several paragraphs and concludes with:

I am sending you all these details in a modest drawing so that with both the written description and the cartoon you volition be able to consider my wishes in this thing. Just if you think that perhaps in that location are too many figures in this for one picture, it is left to yous to reduce them equally you please, provided that you lot do not remove the chief basis, which consists of the 4 figures of Pallas, Diana, Venus and Cupid. If no inconvenience occurs I shall consider myself well satisfied; you are costless to reduce them, but not to add annihilation else. Please be content with this system.

(Paoletti, 360)

Battle Between Honey & Chastity past Perugino

Portraiture must have been a particularly tempting area for patron interference and one wonders what customers thought of such innovations as Leonardo da Vinci's three-quarter view of his subjects or the absence of conventional status symbols like jewellery. I of the bones of contention between the Pope and Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE) while he was painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling was that the artist refused to permit his patron encounter the work until information technology was completed.

Finally, information technology was not unusual for patrons to appear somewhere in the work of art they had commissioned, an instance existence Enrico Scrovegni, kneeling in the Concluding Sentence section of Giotto's frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510 CE) even managed to get in a whole family of senior Medici in his 1475 CE Adoration of the Magi. At the same fourth dimension, the artist might put themselves in the work, run across, for example, the bust of Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455 CE) in his bronze panelled doors of Florence's Baptistery.

Post-Project Reaction

Despite the contractual restrictions, nosotros tin can imagine that many artists tried to push the boundaries of what had been previously agreed upon or simply experimented with novel approaches to a tired subject matter. Some patrons, of grade, may even have encouraged such independence, especially when working with more famous artists. However, even the most renowned artists could get into trouble. Information technology was not unknown, for case, for a fresco not to be appreciated and so exist painted over and and then redone by another artist. Even Michelangelo faced this when completing his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. Some of the clergy objected to the amount of nudes and proposed to supercede them entirely. A compromise was settled on and 'trousers' were painted on the offending figures by another creative person. All the same, the fact that many artists received echo commissions would suggest that patrons were more often satisfied than not with their purchases and that, like today, in that location was a sure respectful deference for creative license.

Patrons certainly could be disappointed by an artist, most unremarkably by them never finishing the work at all, either because they walked out over a disagreement on the design or they only had as well many projects ongoing. Michelangelo fled Rome and the interminable saga that was the design and execution of the tomb of Pope Julius Two (r. 1503-1513 CE), while Leonardo da Vinci was notorious for not finishing commissions only considering his overactive heed lost interest in them after a while. In some cases, the main artist might have deliberately left some parts of the work to be finished by his assistants, some other betoken which a wise patron could baby-sit against in the original contract. In short, though, litigations for breaches of contract were not an uncommon occurrence and, just similar commissioning an creative person today, information technology seems that a Renaissance patron could be delighted, surprised, perplexed, or downright outraged at the finished work of art they had paid for.

This article has been reviewed for accurateness, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1624/patrons--artists-in-renaissance-italy/

0 Response to "Patrons of the Arts in the 14th and 15th Century Included"

Publicar un comentario